Operation Oblivion and Commando Bay

Operation Oblivion

For almost a century after the first group of Chinese came to settle on the West Coast, the Chinese community was marginalized and subject to various kinds of discrimination. Men and women of Chinese descent, even those who were born in Canada, were denied basic citizenship rights, facing limited opportunities, and unable to participate in Canadian society as fellow Canadians. When World War II broke out, young Chinese men and women were turned away from the recruiting offices.

However, as the Japanese seized several British colonies in the Pacific, the Allied forces grew desperate and British Secret Service was looking for soldiers to infiltrate behind enemy lines and assist the resistance fighters. Chinese-Canadian men were thought to be the perfect fit for this daring mission. It was believed the Japanese would not be able to tell their difference from local Asians. Even though some Canadian military officials were worried that if the men survived, they might request citizenship and voting rights, the Allies were desperate to end the Japanese offence.

Recruited in secrecy by the British Secret Service and Canadian military (was it a joint operation? It is necessary to say that these men were trained by the British Secret Service – please verify the fact), 13 Chinese-Canadian men volunteered for the dangerous mission that offered little chance of survival, hence named “Operation Oblivion.” These brave men wanted to fight for the country they called home, even though not recognized as its citizens. They volunteered to fight for world peace and for human rights, hoping that their efforts would gain respect at home and help their families and other Chinese-Canadians obtain full citizenship rights. Now “Operation Oblivion” is recognized as a pivotal part of Canada`s war history and a milestone in recognizing the Chinese community as an integral part of Canada’s society.

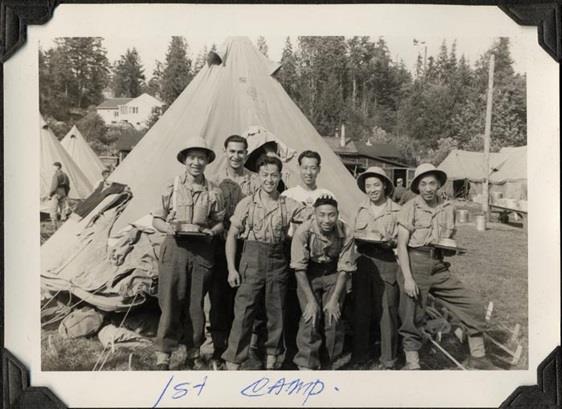

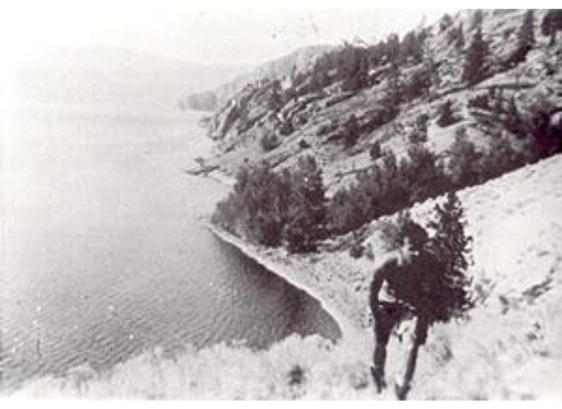

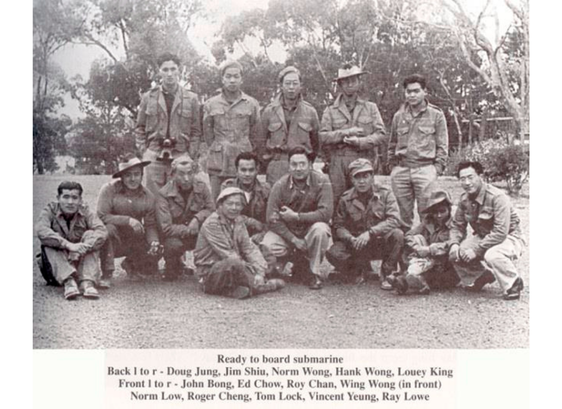

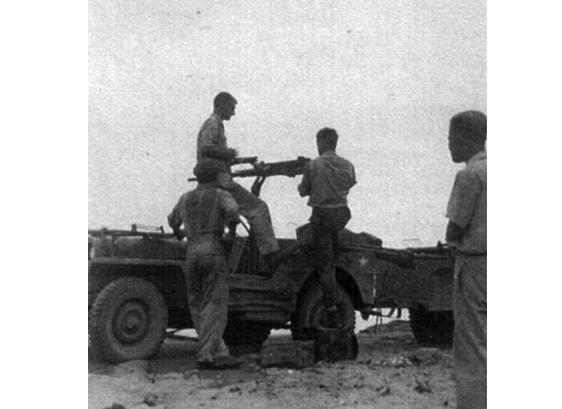

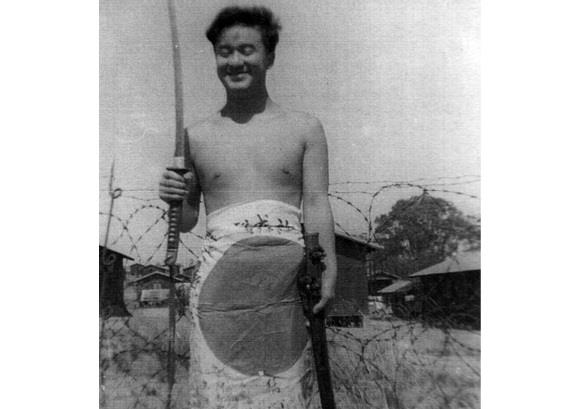

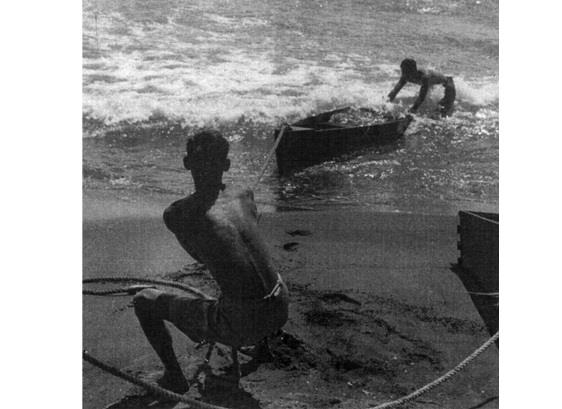

The men started their secret espionage training in June 1944 at Commando Bay, south of Kelowna. They were trained in hand-to-hand combat and acquired jungle survival and assassination skills. Each team member learned a specialty – explosives, tank command, etc., which earned them nicknames like …. The men also had to learn basic Chinese because most did not speak it. After a few months of training, the graduates of the Commando Bay camp went on to further training in Australia, which included training on submarines and parachuting behind enemy lines. A part of the final preparation involving cyanide pills placed inside a tooth in case they got caught by the Japanese during the operation. These men went on to service in India, Ceylon, Malaya and Borneo. Their bravery is testified by the fact that out of this small group, four were awarded the Military Medal for their bravery in action.

After Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, these Chinese Canadian special agents returned to Canada. Together with more than 800 young men and women of Chinese descent who had enlisted in the military, they faced discriminations. These men were sworn to decades of secrecy, not welcomed as war heroes, and not allowed to join the Canadian Legion. The veterans began to actively lobby for citizenship rights with the Chinese-Canadian community behind them. In 1947 the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed by the government and Chinese-Canadians got the right to vote.

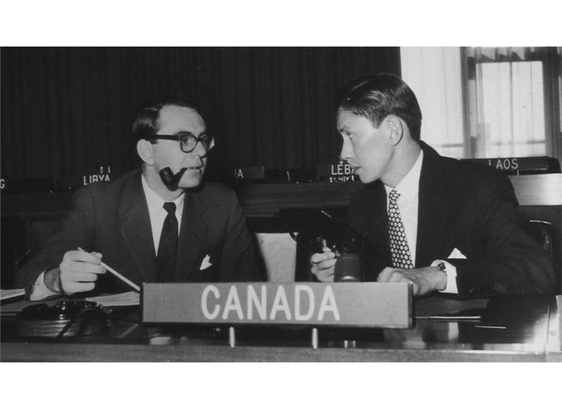

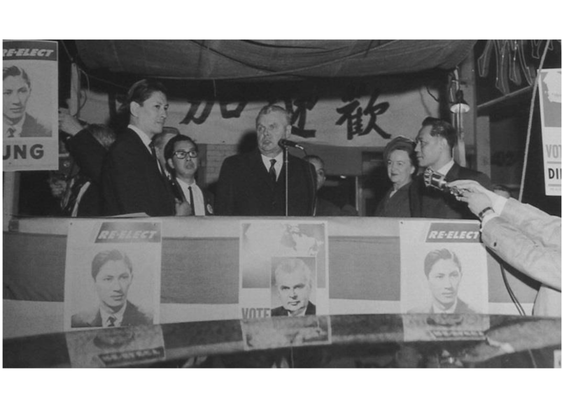

One of the men who volunteered for “Operation Oblivion” was Doug Jung. He entered politics and became the first Chinese-Canadian MP and later Canada`s representative at the United Nations. During the second half of the twentieth century, more and more people began to recognize those Chinese-Canadians who fought for Canada during World War II. The Chinese-Canadian Military Museum was created to recognize the veterans and commemorate their military service.

As recorded by Angeline Waterman of the Okanagan Historical Society, on September 17, 1988, “two houseboats headed north from Penticton to Commando Bay. The passengers, ten survivors of thirteen Chinese Canadian special agents who trained during the summer of 1944 at Commando Bay, were returning with honoured guests to dedicate a bronze plague commemorating their training in the Okanagan and Australia and successful operations in Borneo. Friends greeted each other with great warmth” (“Commando Bay Reunion”). At this ceremony Douglas Jung read Prime Minister Mulroney’s message: “On behalf of the Government of Canada, I wish to extend my warmest congratulations to a very special group of veterans. Not only did this gallant band of Chinese Canadians volunteer for wartime service, they did so knowing that they would be signing up for some extremely dangerous and hazardous missions…”.

遺忘行動

在第一批華人定居西海岸近一個世紀之後,加拿大華人社區一直被邊緣化,並遭受各種歧視。華裔男女,即使在加拿大出生,也被剝奪了基本的公民權利,面對有限的機會,無法像其他加拿大人一樣融入加拿大社會。第二次世界大戰爆發時,年輕的華裔男女在徵兵處被拒之門外。

然而,當日本佔領了太平洋的多個英屬殖民地後,同盟國陷入絕望,英國情報機關正在尋找能夠潛入敵後、協助抵抗力量的士兵。華裔加拿大人被認為是這項大膽任務的最佳人選,因為人們相信日本人無法分辨他們與當地亞洲人的不同。儘管一些加拿大軍方官員擔心這些人如果活下來,可能會要求公民身份和投票權,但在擊退日本的緊迫形勢下,同盟國已顧不得這些顧慮。

在英國情報機關和加拿大軍方的秘密招募下(是否屬聯合行動需進一步確認;必須指出這些人接受過英國情報機關訓練——此處事實需核實),13名華裔加拿大人自願加入這項幾乎沒有生還希望的危險任務,因此被命名為 「遺忘行動」。這些勇敢的年輕人願意為他們稱之為祖國的國家而戰,儘管當時他們並不被承認為公民。他們自願為世界和平與人權而戰,希望他們的付出能夠贏得加拿大社會的尊重,並幫助他們的家人和華裔同胞獲得完整的公民權利。今天,**「遺忘行動」**已被公認為加拿大戰爭史上的關鍵一頁,也是華人社區被認可為加拿大社會重要組成部分的重要里程碑。

1944年6月,這些人開始在基洛納以南的突擊灣(Commando Bay)接受秘密特工訓練。他們學習了徒手格鬥、叢林生存和暗殺技能。每位成員都有專攻——爆破、坦克駕駛等,因此獲得了綽號。由於大多數人不會中文,他們還必須學習基礎中文。幾個月後,突擊灣訓練營的學員前往澳大利亞接受進一步訓練,包括潛艇作戰和傘降敵後的訓練。最後的準備甚至包括在牙齒中安放氰化物膠囊,以便在被日軍俘虜時自盡。這些人隨後被派往印度、錫蘭、馬來亞和婆羅洲。他們的英勇可見一斑——在這個小隊中,就有四人因戰鬥中的勇敢表現而被授予軍事獎章。

1945年8月15日日本投降後,這些華裔加拿大特工返回加拿大。他們與其他800多名參軍的華裔男女一樣,依舊面對歧視。這些退伍軍人被要求對行動保密數十年,不被當作英雄歡迎,甚至不能加入加拿大退伍軍人協會。於是他們開始積極爭取公民權利,並得到整個華裔社區的支持。1947年,加拿大政府廢除了《排華法》,華裔加拿大人獲得了投票權。

參加 「遺忘行動」 的其中一人是鄭天華(Doug Jung)。他後來投身政界,成為首位華裔加拿大國會議員,並代表加拿大出任聯合國代表。進入20世紀下半葉,越來越多的人開始認可那些在二戰中為加拿大而戰的華裔加拿大人。為了紀念這些退伍軍人,加拿大華裔軍事博物館應運而生。

據奧肯那根歷史協會的安吉琳·沃特曼(Angeline Waterman)記載,1988年9月17日,「兩艘屋船從彭蒂克頓(Penticton)駛向突擊灣。乘客中包括13名華裔加拿大特工中的10位倖存者,他們攜帶嘉賓返回此地,參加紀念儀式,獻上青銅紀念牌,以紀念他們在奧肯那根和澳大利亞的訓練以及在婆羅洲的成功任務。朋友們彼此熱烈相擁。」(《突擊灣重聚》)在這場儀式上,鄭天華宣讀了加拿大總理穆羅尼的致辭:「謹代表加拿大政府,向這一特殊的退伍軍人群體致以最熱烈的祝賀。這支英勇的華裔加拿大隊伍不僅自願參軍服役,而且明知自己將要承擔極其危險和艱險的任務……」

史實與展板由 OCCA 於 2016 年 5 月整理和製作

遗忘行动

在第一批华人定居西海岸近一个世纪之后,加拿大华人社区一直被边缘化,并遭受各种歧视。华裔男女,即使在加拿大出生,也被剥夺了基本的公民权利,面对有限的机会,无法像其他加拿大人一样融入加拿大社会。第二次世界大战爆发时,年轻的华裔男女在征兵处被拒之门外。

然而,当日本占领了太平洋的多个英属殖民地后,同盟国陷入绝望,英国情报机关正在寻找能够潜入敌后、协助抵抗力量的士兵。华裔加拿大人被认为是这项大胆任务的最佳人选,因为人们相信日本人无法分辨他们与当地亚洲人的不同。尽管一些加拿大军方官员担心这些人如果活下来,可能会要求公民身份和投票权,但在击退日本的紧迫形势下,同盟国已顾不得这些顾虑。

在英国情报机关和加拿大军方的秘密招募下(是否属联合行动需进一步确认;必须指出这些人接受过英国情报机关训练——此处事实需核实),13名华裔加拿大人自愿加入这项几乎没有生还希望的危险任务,因此被命名为 “遗忘行动”。这些勇敢的年轻人愿意为他们称之为祖国的国家而战,尽管当时他们并不被承认为公民。他们自愿为世界和平与人权而战,希望他们的付出能够赢得加拿大社会的尊重,并帮助他们的家人和华裔同胞获得完整的公民权利。今天,**“遗忘行动”**已被公认为加拿大战争史上的关键一页,也是华人社区被认可为加拿大社会重要组成部分的重要里程碑。

1944年6月,这些人开始在基洛纳以南的突击湾(Commando Bay)接受秘密特工训练。他们学习了徒手格斗、丛林生存和暗杀技能。每位成员都有专攻——爆破、坦克驾驶等,因此获得了绰号。由于大多数人不会中文,他们还必须学习基础中文。几个月后,突击湾训练营的学员前往澳大利亚接受进一步训练,包括潜艇作战和伞降敌后的训练。最后的准备甚至包括在牙齿中安放氰化物胶囊,以便在被日军俘虏时自尽。这些人随后被派往印度、锡兰、马来亚和婆罗洲。他们的英勇可见一斑——在这个小队中,就有四人因战斗中的勇敢表现而被授予军事奖章。

1945年8月15日日本投降后,这些华裔加拿大特工返回加拿大。他们与其他800多名参军的华裔男女一样,依旧面对歧视。这些退伍军人被要求对行动保密数十年,不被当作英雄欢迎,甚至不能加入加拿大退伍军人协会。于是他们开始积极争取公民权利,并得到整个华裔社区的支持。1947年,加拿大政府废除了《排华法》,华裔加拿大人获得了投票权。

参加 “遗忘行动” 的其中一人是郑天华(Doug Jung)。他后来投身政界,成为首位华裔加拿大国会议员,并代表加拿大出任联合国代表。进入20世纪下半叶,越来越多的人开始认可那些在二战中为加拿大而战的华裔加拿大人。为了纪念这些退伍军人,加拿大华裔军事博物馆应运而生。

据奥肯那根历史协会的安吉琳·沃特曼(Angeline Waterman)记载,1988年9月17日,“两艘屋船从彭蒂克顿(Penticton)驶向突击湾。乘客中包括13名华裔加拿大特工中的10位幸存者,他们携带嘉宾返回此地,参加纪念仪式,献上青铜纪念牌,以纪念他们在奥肯那根和澳大利亚的训练以及在婆罗洲的成功任务。朋友们彼此热烈相拥。”(《突击湾重聚》)在这场仪式上,郑天华宣读了加拿大总理穆罗尼的致辞:“谨代表加拿大政府,向这一特殊的退伍军人群体致以最热烈的祝贺。这支英勇的华裔加拿大队伍不仅自愿参军服役,而且明知自己将要承担极其危险和艰险的任务……”

史实与展板由 OCCA 于 2016 年 5 月整理和制作

Stories and panel developed by OCCA in May 2016