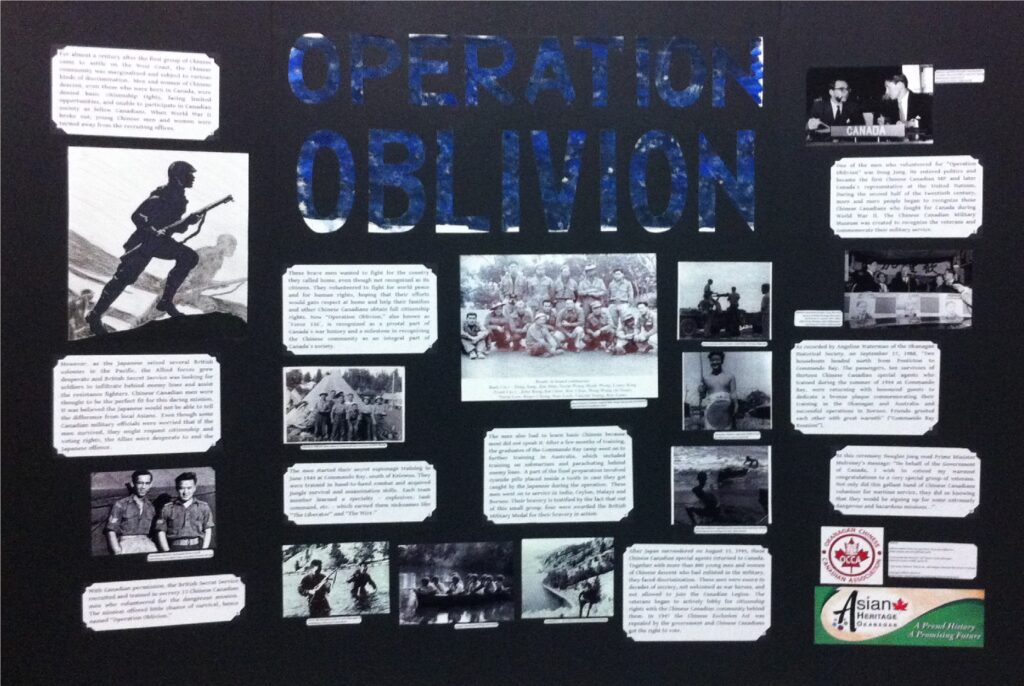

Operation Oblivion

For almost a century after the first group of Chinese came to settle on the West Coast, the Chinese community was marginalized and subject to various kinds of discrimination. Men and women of Chinese descent, even those who were born in Canada, were denied basic citizenship rights, facing limited opportunities, and unable to participate in Canadian society as fellow Canadians. When World War II broke out, young Chinese men and women were turned away from the recruiting offices.

However, as the Japanese seized several British colonies in the Pacific, the Allied forces grew desperate and British Secret Service was looking for soldiers to infiltrate behind enemy lines and assist the resistance fighters. Chinese-Canadian men were thought to be the perfect fit for this daring mission. It was believed the Japanese would not be able to tell their difference from local Asians. Even though some Canadian military officials were worried that if the men survived, they might request citizenship and voting rights, the Allies were desperate to end the Japanese offence.

Recruited in secrecy by the British Secret Service and Canadian military (was it a joint operation? It is necessary to say that these men were trained by the British Secret Service – please verify the fact), 13 Chinese-Canadian men volunteered for the dangerous mission that offered little chance of survival, hence named “Operation Oblivion.” These brave men wanted to fight for the country they called home, even though not recognized as its citizens. They volunteered to fight for world peace and for human rights, hoping that their efforts would gain respect at home and help their families and other Chinese-Canadians obtain full citizenship rights. Now “Operation Oblivion” is recognized as a pivotal part of Canada`s war history and a milestone in recognizing the Chinese community as an integral part of Canada`s society.

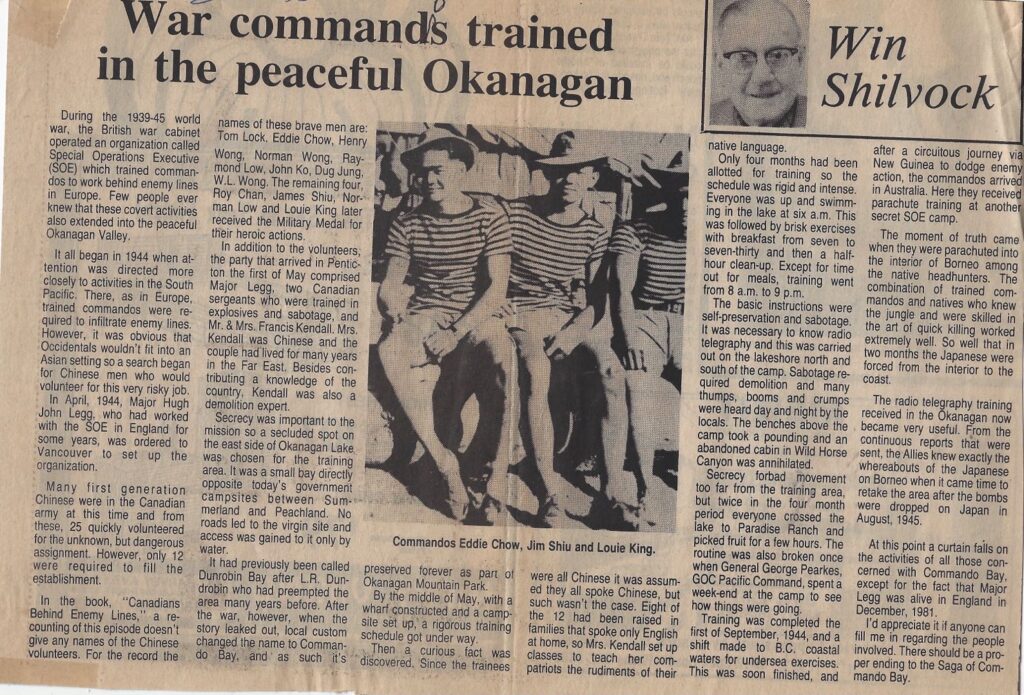

The men started their secret espionage training in June 1944 at Commando Bay, south of Kelowna. They were trained in hand-to-hand combat and acquired jungle survival and assassination skills. Each team member learned a specialty – explosives, tank command, etc., which earned them nicknames like …. The men also had to learn basic Chinese because most did not speak it. After a few months of training, the graduates of the Commando Bay camp went on to further training in Australia, which included training on submarines and parachuting behind enemy lines. A part of the final preparation involving cyanide pills placed inside a tooth in case they got caught by the Japanese during the operation. These men went on to service in India, Ceylon, Malaya and Borneo. Their bravery is testified by the fact that out of this small group, four were awarded the Military Medal for their bravery in action.

After Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, these Chinese Canadian special agents returned to Canada. Together with more than 800 young men and women of Chinese descent who had enlisted in the military, they faced discriminations. These men were sworn to decades of secrecy, not welcomed as war heroes, and not allowed to join the Canadian Legion. The veterans began to actively lobby for citizenship rights with the Chinese-Canadian community behind them. In 1947 the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed by the government and Chinese-Canadians got the right to vote.

One of the men who volunteered for “Operation Oblivion” was Doug Jung. He entered politics and became the first Chinese-Canadian MP and later Canada`s representative at the United Nations. During the second half of the twentieth century, more and more people began to recognize those Chinese-Canadians who fought for Canada during World War II. The Chinese-Canadian Military Museum was created to recognize the veterans and commemorate their military service.

As recorded by Angeline Waterman of the Okanagan Historical Society, on September 17, 1988, “two houseboats headed north from Penticton to Commando Bay. The passengers, ten survivors of thirteen Chinese Canadian special agents who trained during the summer of 1944 at Commando Bay, were returning with honoured guests to dedicate a bronze plague commemorating their training in the Okanagan and Australia and successful operations in Borneo. Friends greeted each other with great warmth” (“Commando Bay Reunion”). At this ceremony Douglas Jung read Prime Minister Mulroney’s message: “On behalf of the Government of Canada, I wish to extend my warmest congratulations to a very special group of veterans. Not only did this gallant band of Chinese Canadians volunteer for wartime service, they did so knowing that they would be signing up for some extremely dangerous and hazardous missions…”.

stories and panel developed by OCCA in May 2016